Guest Blogged by Coleen Rowley, FBI whistleblower, TIME's 2002 'Person of the Year'

Guest Blogged by Coleen Rowley, FBI whistleblower, TIME's 2002 'Person of the Year'

Back in December 2007, when I wrote "Torture is Wrong, Illegal and It Doesn't Work," I mentioned that "the FBI agent who reportedly had the best chance of foiling the 9/11 plot, Ali Soufan, the only Arabic-speaking agent in New York and one of only eight in the country, and who has since resigned from the FBI, could and should tell people the truth of how the CIA's tactics were counterproductive."

Well guess what?! HE FINALLY DID SO ON WEDNESDAY! The points Soufan makes are very instructive as our country begins to unravel the differences between the fictional world of Hollywood's "Jack Bauer," and the real world dilemmas and questions of morality and legality as faced by actual intelligence and law enforcement officers.

"My Tortured Decision" is how former FBI Agent Soufan titled his New York Times op-ed, speaking out to specifically refute a number of Dick Cheney's lies about how torture "worked." The truth, according to Soufan, is quite the opposite from how Cheney continues to paint it...

By ALI SOUFAN

FOR seven years I have remained silent about the false claims magnifying the effectiveness of the so-called enhanced interrogation techniques like waterboarding. I have spoken only in closed government hearings, as these matters were classified. But the release last week of four Justice Department memos on interrogations allows me to shed light on the story, and on some of the lessons to be learned.

One of the most striking parts of the memos is the false premises on which they are based. The first, dated August 2002, grants authorization to use harsh interrogation techniques on a high-ranking terrorist, Abu Zubaydah, on the grounds that previous methods hadn't been working. The next three memos cite the successes of those methods as a justification for their continued use.

It is inaccurate, however, to say that Abu Zubaydah had been uncooperative. Along with another F.B.I. agent, and with several C.I.A. officers present, I questioned him from March to June 2002, before the harsh techniques were introduced later in August. Under traditional interrogation methods, he provided us with important actionable intelligence.

We discovered, for example, that Khalid Shaikh Mohammed was the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks. Abu Zubaydah also told us about Jose Padilla, the so-called dirty bomber. This experience fit what I had found throughout my counterterrorism career: traditional interrogation techniques are successful in identifying operatives, uncovering plots and saving lives.

There was no actionable intelligence gained from using enhanced interrogation techniques on Abu Zubaydah that wasn't, or couldn't have been, gained from regular tactics. In addition, I saw that using these alternative methods on other terrorists backfired on more than a few occasions --- all of which are still classified. The short sightedness behind the use of these techniques ignored the unreliability of the methods, the nature of the threat, the mentality and modus operandi of the terrorists, and due process.

Defenders of these techniques have claimed that they got Abu Zubaydah to give up information leading to the capture of Ramzi bin al-Shibh, a top aide to Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, and Mr. Padilla. This is false. The information that led to Mr. Shibh's capture came primarily from a different terrorist operative who was interviewed using traditional methods. As for Mr. Padilla, the dates just don't add up: the harsh techniques were approved in the memo of August 2002, Mr. Padilla had been arrested that May.

One of the worst consequences of the use of these harsh techniques was that it reintroduced the so-called Chinese wall between the C.I.A. and F.B.I., similar to the communications obstacles that prevented us from working together to stop the 9/11 attacks. Because the bureau would not employ these problematic techniques, our agents who knew the most about the terrorists could have no part in the investigation. An F.B.I. colleague of mine who knew more about Khalid Shaikh Mohammed than anyone in the government was not allowed to speak to him.

It was the right decision to release these memos, as we need the truth to come out. This should not be a partisan matter, because it is in our national security interest to regain our position as the world's foremost defenders of human rights. Just as important, releasing these memos enables us to begin the tricky process of finally bringing these terrorists to justice.

The debate after the release of these memos has centered on whether C.I.A. officials should be prosecuted for their role in harsh interrogation techniques. That would be a mistake. Almost all the agency officials I worked with on these issues were good people who felt as I did about the use of enhanced techniques: it is un-American, ineffective and harmful to our national security.

Fortunately for me, after I objected to the enhanced techniques, the message came through from Pat D'Amuro, an F.B.I. assistant director, that "we don't do that," and I was pulled out of the interrogations by the F.B.I. director, Robert Mueller (this was documented in the report released last year by the Justice Department's inspector general).

My C.I.A. colleagues who balked at the techniques, on the other hand, were instructed to continue. (It's worth noting that when reading between the lines of the newly released memos, it seems clear that it was contractors, not C.I.A. officers, who requested the use of these techniques.)

As we move forward, it's important to not allow the torture issue to harm the reputation, and thus the effectiveness, of the C.I.A. The agency is essential to our national security. We must ensure that the mistakes behind the use of these techniques are never repeated. We're making a good start: President Obama has limited interrogation techniques to the guidelines set in the Army Field Manual, and Leon Panetta, the C.I.A. director, says he has banned the use of contractors and secret overseas prisons for terrorism suspects (the so-called black sites). Just as important, we need to ensure that no new mistakes are made in the process of moving forward --- a real danger right now.

Ali Soufan was an F.B.I. supervisory special agent from 1997 to 2005.

Former Agent Soufan is to be applauded for speaking out after seven years, something even FBI Director Mueller has not really found the courage to do (although Mueller was forced recently to truthfully admit that no attack on America has been disrupted as a result of intelligence obtained through "enhanced techniques").

I agree with almost everything Soufan writes except his wish that no agency officials at the CIA be prosecuted because almost all of them were "good people who felt as I did about the use of enhanced techniques: it is un-American, ineffective and harmful to our national security." But he says (implying, whether he realizes it or not, the Nuremberg Defense), they simply had to follow orders.

No disagreement exists on how difficult--literally between a rock and a hard place, any government employee finds him or herself when given illegal and wrongful orders. When the "green light" was turned on to torture, it was akin to the terrible situation that helicopter pilot Hugh Thompson Jr. found himself in when he looked down from his helicopter to see Lt. William Calley and his men massacring Vietnamese villagers at My Lai. It was similar to the horrible situation that Daniel Ellsberg found himself in when he realized what was in the Pentagon Papers undercut several presidential administrations' lies in launching and keeping the Vietnam War going. There is presently no protection whatsoever for government whistleblowers who find themselves in these situations, especially those who work in intelligence. As it stands now, if you follow your conscience and speak out internally, you will, at the very least, be retaliated against, possibly fired and at worst, if you speak out publicly as DOJ Attorney Thomas Tamm did about Bush's illegal warrantless monitoring, you will subject yourself to criminal prosecution as a "leaker." So it's quite understandable how former Agent Soufan sees the choice as going along with the illegal orders or resigning to avoid personal direct involvement but maintaining silent complicity.

As I wrote three days ago in my own NY Times op-ed: "It's true, and proved repeatedly in social psychology experiments, that otherwise good people will tend to conform to authority. It's true that people, under such circumstances, often fail to listen to their consciences. But don't conflate this obedience factor with not being able to appreciate the wrongfulness."

On my own personal note, the final thing I did the day I retired from the FBI (in December, 2004) was e-mail my last mini-legal lecture to every employee in the entire Minneapolis FBI office warning my former colleagues how the "green light" would inevitably go out, and when that happens, it always leaves the little guys holding the bag. Nearly all the little guys in government knew, by that time, about the green-but-evil light that had been turned on. And even though the FBI was not going along with the torture tactics, it was going overboard in other areas involving massive data collection on American citizens. Because I was already persona non grata in the FBI for having spoken out about wrongful over-reactions and counterproductive responses after 9/11, I would only catch others' hushed whispers about the "green light" stuff, but I think nearly everyone was well aware. That last warning was the least I could do as I walked out the door but in all probability, many who got my goodbye e-mail immediately deleted it as they dreaded any reminder about "green lights" that always go out.

In the criminal justice system, the mitigating circumstances of such difficult, untenable situations and choices of subordinate government employees are not irrelevant and would be evaluated. In the course of criminal investigation, it's common to give immunity to underlings who, it is found, had little or no choice but to follow orders and are therefore not as culpable as those in power giving the orders. Additionally, once the truth of the facts is ascertained, there's room for all kinds of humanitarian arguments as to what, if any, are proper "punishments." With respect to those on the receiving end of illegal orders, I'd volunteer to help explain how absolutely difficult their situation is. I'd even help the defense find a social psychologist or two who can demonstrate what all the experiments on "group think" and "obedience to authority" have proven with regard to human behavior. But this would go to evaluating relative responsibility and mitigating punishments and should not be used as a reason to jump over the most crucial first phase of the criminal justice process: the fact-finding ascertainment of truth.

We've already heard enough from fictional characters like Jack Bauer. It's time to hear from real agents who operated in the real world like Ali Soufan. After we hear the facts, then let's also hear the mitigating circumstances of how difficult, how very difficult it is not to follow a President's orders in the real world.

===

Coleen Rowley worked as an FBI Special Agent and legal counsel for more than 20 years until retiring in 2004. Following 9/11, after blowing the whistle on failures at the FBI which led up to the attacks, she testified to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee about endemic problems facing the both the agency and the intelligence community. In 2002 she was one of three whistleblowers named TIME magazine's "Persons of the Year."

'Green News Report' 1/6/26

'Green News Report' 1/6/26

Trump's War on Venezuela is About Ego, Power, Creation of 'Alien Enemies': 'BradCast' 1/5/26

Trump's War on Venezuela is About Ego, Power, Creation of 'Alien Enemies': 'BradCast' 1/5/26 Sunday 'Peace President' Toons

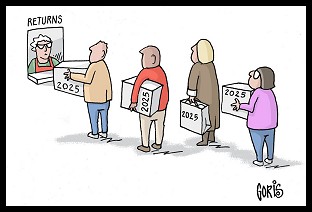

Sunday 'Peace President' Toons Sunday 'Many Happy Returns' Toons

Sunday 'Many Happy Returns' Toons Have a Holly Jolly Somehow

Have a Holly Jolly Somehow 'Tis the Sunday Before Christmas Toons

'Tis the Sunday Before Christmas Toons Old Man Shouts at People from White House for 20 Minutes, and Other Year-End Matters: 'BradCast' 12/18/25

Old Man Shouts at People from White House for 20 Minutes, and Other Year-End Matters: 'BradCast' 12/18/25 'Green News Report' 12/18/25

'Green News Report' 12/18/25 SCOTUS Ruling a How-To for Unlawful Gerrymandering on 'Eve' of Critical Election Year: BradCast' 12/17/25

SCOTUS Ruling a How-To for Unlawful Gerrymandering on 'Eve' of Critical Election Year: BradCast' 12/17/25 Bricks in the Wall: 'BradCast' 12/16/25

Bricks in the Wall: 'BradCast' 12/16/25 'Green News Report' 12/16/25

'Green News Report' 12/16/25 'This One Goes to 11': Weekend of Violence, Murder of Rob Reiner: 'BradCast' 12/15

'This One Goes to 11': Weekend of Violence, Murder of Rob Reiner: 'BradCast' 12/15 Sunday 'WTF?' Toons

Sunday 'WTF?' Toons Trump Now Losing One Battle After Another: 'BradCast' 12/11/25

Trump Now Losing One Battle After Another: 'BradCast' 12/11/25 'Green News Report' 12/11/25

'Green News Report' 12/11/25 Dems Continue Stunning 2025 Election Streak: 'BradCast' 12/10/25

Dems Continue Stunning 2025 Election Streak: 'BradCast' 12/10/25 Petrostates and Propa-gandists Undermining Climate Science: 'BradCast' 12/9/25

Petrostates and Propa-gandists Undermining Climate Science: 'BradCast' 12/9/25 The High Cost of Trump's Terrible Policy Making: 'BradCast' 12/8/25

The High Cost of Trump's Terrible Policy Making: 'BradCast' 12/8/25 Dems Fight to Avoid GOP's Year-End Health Care Cliff: 'BradCast' 12/4/25

Dems Fight to Avoid GOP's Year-End Health Care Cliff: 'BradCast' 12/4/25 A 'Flashing Red Warning Sign' for GOP: 'BradCast' 12/3/25

A 'Flashing Red Warning Sign' for GOP: 'BradCast' 12/3/25 Hegseth, War Crimes and DoD's 'Politicization Death Spiral': 'BradCast' 12/2/25

Hegseth, War Crimes and DoD's 'Politicization Death Spiral': 'BradCast' 12/2/25 Follow the

Follow the  With Thanks, No Kings and Good Cheer

With Thanks, No Kings and Good Cheer

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL