As noted previously, I am originally from (and embarrassed for) St. Louis County, MO. Recently, I spoke to a family member for the first time since the mess blew up in Ferguson, and she told me that, while troubled by it, she was willing to "wait until all the information came out" before passing judgment one way or another.

As noted previously, I am originally from (and embarrassed for) St. Louis County, MO. Recently, I spoke to a family member for the first time since the mess blew up in Ferguson, and she told me that, while troubled by it, she was willing to "wait until all the information came out" before passing judgment one way or another.

But, as I explained, there is no need to wait. Judgment may already be passed. No matter we may later learn, the police in Ferguson and St. Louis County broke the law and violated their own written policies by not detailing what happened in an Incident Report after Ferguson Police officer Darren Wilson gunned down Michael Brown, an unarmed African-American teenager, in the middle of the street more than two weeks ago.

That, pretty much, tells you all you need to know in order to pass judgment. Whatever happened during that tragic afternoon, the local police immediately began either covering it up or lying about it. How else to explain the lack of an Incident Report, which must be filed after any such incident?

After the shooting, many wondered why the police hadn't released their Incident Report of the event to the public. After all, they released a full report, and surveillance video, from a convenience store incident where they allege Brown had shoplifted some cigars just minutes prior to his killing. So, where was the Incident Report describing the matter in which Wilson shot Brown dead just minutes later during an unrelated confrontation on the street? We now know there was no such report, at least according to the documents finally released by the police themselves. The laughably terse "Incident Report" eventually released by the St. Louis County Police (the Ferguson Police never released one of their own), includes little more than a date and an address where the shooting occurred, but no other information about what actually happened.

Moreover, dates on the few documents released make it fairly plain that the Incident Report released to the public, bereft of actual information about the, ya know, incident, was filed some two weeks after the actual killing.

In a long, detailed and meticulously-documented post at PhotographyIsNotACrime.com (PINAC) on Monday, Charlie Grapski outlines a string of public records requests he filed with Ferguson and St. Louis County police in an attempt to get at the Incident Report (and other documents) related to Brown's shooting.

The upshot: there were no contemporaneous reports of the incident at best, or, more nefariously, there was an Incident Report, but the local police have since destroyed it, or are otherwise covering the entire affair up by not releasing it to the public and lying about it...

As Grapski recounts, the police attempted to claim to the ACLU and others who had also filed public records requests to obtain the documents under Missouri's Sunshine Law, that the Incident Report in this case was exempt from such requests, because the matter of the shooting is currently under investigation. When it was explained that Incident Reports are not exempt from such requests, they stalled, but eventually produced one, with little more than the time and address of the incident.

Grapski, who is heading up PINAC's Open Records Project, explains that under 610.100 of the Revised Missouri Statutes, an Incident Report is defined as [emphasis added] "a record of a law enforcement agency consisting of the date, time, specific location, name of the victim and immediate facts and circumstances surrounding the initial report of a crime or incident, including any logs of reported crimes, accidents and complaints maintained by that agency."

While the investigative report of the incident, theoretically being compiled now by the St. Louis County Prosecutor, might be exempt from such requests, the Incident Report of the actual police stop and fatal shooting is not exempt, and it must contain, as described by state statutes, the "immediate facts and circumstances surrounding the initial report of a crime or incident". The documents released by the Ferguson and St. Louis County police departments contain no such information.

That lack of information is in violation of the Ferguson Police's own written procedures, also obtained by Grapski, which specifically detail when "officers are required to complete written police reports", such as following incidents that involve "violations of law or ordinance"; "arrests for any charge"; "use of force"; and "any situation which may result in civil action or complaint against the department".

In other words, Ferguson's own procedures require a full documentation of the incident that resulted in Darren Wilson shooting Michael Brown at least six times, resulting in his death.

According to the same documents, "Information required in reports" includes "an officer's narrative as to the nature, facts and officer actions."

None of that was included in the Incident Report released to the public. Grapski tells me, "Yes, they clearly created this report --- specially and different than all others in past --- to produce a record, just not the required one."

So, either the police violated the law and their own written procedures by not documenting the facts of the incident, or they have violated state public records laws by not releasing the actual, contemporaneous Incident Report(s) filed after the shooting.

Last week, NBC News reported that the Ferguson police claim they did not file a report because, according to the County Prosecutor's office, "they turned the case over to St. Louis County police almost immediately."

Still, St. Louis County Police should then have created such a report, offering a full accounting of the details of the incident. If they did so, they have not released that report to the public.

The idea that Wilson may not have filed a report at all because it would have violated his Fifth Amendment right not to testify against himself has also been floated as a possible explanation for why there is no Incident Report from the Ferguson Police.

But, Grapski explains, "if an officer does invoke their fifth amendment right, they must do so explicitly and formally. Thus if such an invocation of the right against providing self-incriminating testimony occurred on the part of Officer Wilson there would, again, have to be a public record to this effect. So I made that request of the Ferguson Police Department. In their response, that there was no such record, they have thus answered the question: No, Wilson has not invoked the fifth amendment."

Grapski details how similar documentary information about the incident is also missing from other records he finally obtained from the St. Louis County Police Department in response to other other open records requests.

"Now we also have the evidence to demonstrate that not only one, but two, police agencies -- and thus the officials in charge of those agencies -- are willing to thwart the law, deny the public its rights, and claim effectively they are 'above' the law," he writes. "All this in an effort to cover-up and conceal from the public just what happened that day in the streets of Ferguson."

"This is clear evidence that this incident is being treated DIFFERENTLY than all other incidents --- and that the Departments, not just Officer Wilson, are willing to violate both the policy and law to withhold this information from the public --- even though it is their legal duty to produce it and our right to obtain it," Grapski concludes.

It may be appropriate to wait until "all the facts are in" to determine whether Officer Wilson, who is on paid administrative leave, is actually guilty of the crime of murder. But, as to whether the local police are either covering up for something or simply violating the law in the aftermath of whatever happened that day, it seems there can be little doubt.

In criminal cases, we don't wait until the evidence is created long after the fact, or massaged by a local prosecutor with direct ties to the folks he is supposed to be prosecuting. Any such "evidence" that might emerge hereafter must be regarded as suspect, at this time, given the fact that the contemporaneous evidentiary record that was supposed to be compiled and made available to the public by law enforcement is either missing or was never documented and compiled in the first place. Either way, all of that makes the police suspect and, as likely, an accessory to a crime.

There may have been a perfectly good reason for Wilson to shoot Brown dead in the streets of Ferguson, even if such a reason, at this point, given the various testimony of eyewitness to the shooting, and the police behavior ever since, becomes more and more difficult to imagine with each passing day. There is no reason, however, to cover up whatever happened, unless one is hoping to cover up a crime. And that, in and of itself, is also a crime for which someone must be held accountable.

UPDATE 8/27/2014: See my KPFK/Pacifica Radio interview with Grapski --- who tells me that based on evidence he's received from officials so far, he believes "it's more likely than not" that an actual Incident Report of the event was created by the police, but that "they have withheld it" --- now right here...

Sunday 'Cricket's Revenge' Toons

Sunday 'Cricket's Revenge' Toons NOEM ICED AT DHS:

NOEM ICED AT DHS: 'Green News Report' 3/5/26

'Green News Report' 3/5/26

Why Are We In Iran? And How Do We Get Out?; Also: Primary Results in TX, NC, AR: 'BradCast' 3/4/26

Why Are We In Iran? And How Do We Get Out?; Also: Primary Results in TX, NC, AR: 'BradCast' 3/4/26 No Way Home: Trump's Iran War a Spreading, Chaotic, Deadly, Disaster: 'BradCast'

No Way Home: Trump's Iran War a Spreading, Chaotic, Deadly, Disaster: 'BradCast'  'Green News Report' 3/3/26

'Green News Report' 3/3/26 Trump Attacks Iran in 'Operation Epstein Fury': 'BradCast' 3/2/26

Trump Attacks Iran in 'Operation Epstein Fury': 'BradCast' 3/2/26 Sunday 'No, More Wars!' Toons

Sunday 'No, More Wars!' Toons 'Green News Report' 2/26/26

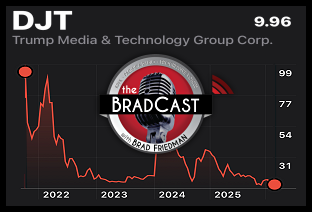

'Green News Report' 2/26/26 Trump's Unlawful Tariffs, Failed Media Co., Corrupt SCOTUS: 'BradCast' 2/26/26

Trump's Unlawful Tariffs, Failed Media Co., Corrupt SCOTUS: 'BradCast' 2/26/26 The State of the Union is ... Insane. So is Trump: 'BradCast' 2/25/26

The State of the Union is ... Insane. So is Trump: 'BradCast' 2/25/26 FCC's New 'Threat'; DOJ's 'Missing' Trump 'Rape' Docs: 'BradCast' 2/24/26

FCC's New 'Threat'; DOJ's 'Missing' Trump 'Rape' Docs: 'BradCast' 2/24/26 Aileen Cannon May be Covering Up Evidence of Trump Rape: 'BradCast' 2/23/26

Aileen Cannon May be Covering Up Evidence of Trump Rape: 'BradCast' 2/23/26 DOJ Hiding Evidence of Trump Rape, Assault Allegations: 'BradCast' 2/19/26

DOJ Hiding Evidence of Trump Rape, Assault Allegations: 'BradCast' 2/19/26 'No More Fig Leaves': Antisemitism Rising Inside MAGA, GOP: 'BradCast' 2/18/26

'No More Fig Leaves': Antisemitism Rising Inside MAGA, GOP: 'BradCast' 2/18/26 'SAVE America Act' Designed to Save GOP, Undermine Democracy: 'BradCast' 2/17/26

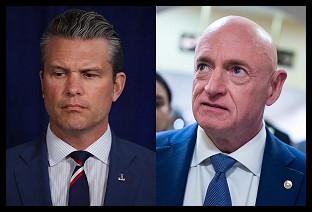

'SAVE America Act' Designed to Save GOP, Undermine Democracy: 'BradCast' 2/17/26 Court Blocks Hegseth Censure of Sen. Kelly

Court Blocks Hegseth Censure of Sen. Kelly

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK

VA GOP VOTER REG FRAUDSTER OFF HOOK Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA

Criminal GOP Voter Registration Fraud Probe Expanding in VA DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST

DOJ PROBE SOUGHT AFTER VA ARREST Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens

Arrest in VA: GOP Voter Reg Scandal Widens ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC

ALL TOGETHER: ROVE, SPROUL, KOCHS, RNC LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States'

LATimes: RNC's 'Fired' Sproul Working for Repubs in 'as Many as 30 States' 'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States

'Fired' Sproul Group 'Cloned', Still Working for Republicans in At Least 10 States FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL

FINALLY: FOX ON GOP REG FRAUD SCANDAL COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION

COLORADO FOLLOWS FLORIDA WITH GOP CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL

CRIMINAL PROBE LAUNCHED INTO GOP VOTER REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL IN FL Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV

Brad Breaks PA Photo ID & GOP Registration Fraud Scandal News on Hartmann TV  CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM

CAUGHT ON TAPE: COORDINATED NATIONWIDE GOP VOTER REG SCAM CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM

CRIMINAL ELECTION FRAUD COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST GOP 'FRAUD' FIRM RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL

RICK SCOTT GETS ROLLED IN GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD SCANDAL VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV

VIDEO: Brad Breaks GOP Reg Fraud Scandal on Hartmann TV RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD

RNC FIRES NATIONAL VOTER REGISTRATION FIRM FOR FRAUD EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud

EXCLUSIVE: Intvw w/ FL Official Who First Discovered GOP Reg Fraud GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL

GOP REGISTRATION FRAUD FOUND IN FL